We open on a severed Transformer’s head hurtling towards a busy T intersection in Philadelphia. There, a Bud Light delivery truck is speeding through the carnage.

It’s going fast, but just not fast enough and the Transformer’s steel skull collects the tail-end of our truck and explodes. Tragically, hundreds of bright blue Bud Light bottles have scattered across the tarmac. The camera goes in for a close up. Under flaming wreckage and tangled wires we see the beautifully packaged Bud Lights, now destroyed.

Our hero, Mark Wahlberg, greasy, dusty and sweaty from blowing up his robo nemesis is thirsty. So he cracks open one of the Bud Lights. Froth explodes from the bottle. Mark chugs half of it before smashing the bottle on the ground.

This was just one example of product placement from the Transformers series. In fact, in (former commercial director) Michael Bay’s filmography there have been some 555 product placements counted. Some overt and verging on a Wayne’s World-esque parody. Some more subtle, almost tucked away in a scene’s background. But most are bereft of any idea, hacky and ham-fisted. How can this style of product placement be anything other than comically ineffective?

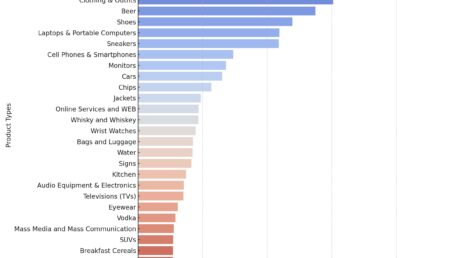

Apparently though, it’s not. Just recently YouGov published figures which measured the value of various product placements in season four of Stranger Things. Lacoste picked up $1.8 million in value for the season. Regardless of how they came up with those numbers, it got me thinking, have I been wrong about the effectiveness of product placement?

Enter persuasion knowledge

One explanation for my aversion to overt product placements may be a phenomenon known as persuasion knowledge. This has been explored by numerous researchers over the years, but the general consensus is that when a consumer is aware they’re being persuaded, they generally develop “less favorable evaluations of marketer actions”.

In line with this, Cristel Antonia Russell from San Diego State University, argues product placements can be more powerful than traditional advertisements, provided they are not “perceived as persuasive messages”.

Put simply, the more subtle product placements are actually the more effective ones. The ham-fisted and over the top examples (like the one we started this piece with) are likely to produce worse results.

The power of the spoken word

Research has found that verbal product placement may be the most effective method, with product placements in which the product or brand name is spoken, but not shown, having the most influence on consumers. They are more likely to be noticed by viewers, and are less likely to trigger persuasion knowledge. For a brilliant example of verbal product placement, look no further than Carrie Bradshaw and Sex in the City. After all, where would she have been without her Manolos!? Sixteen mentions across 94 episodes – and brand sales tripled.

Interestingly, verbal product placements can also improve a brand’s digital presence. Research on nearly 3,000 product placements for 99 brands found that “prominent product placement activities – especially verbal placements – are associated with increases in both online conversations and web traffic for the brand”.

So, if instead of an exploding Bud Light truck and flaming product shots, Mark Wahlberg had casually ordered a Bud Light in one of the movie’s quieter moments – the studies suggest Bud’s parent company Anheuser-Busch would have got better results.

What next for product placement?

Well, unfortunately things are only going to get more visual.

Ryff is a platform which uses AI to “automatically find the right placement opportunity and iterate near instantly for different demographic segments”. Effectively, the AI analyses video files frame-by-frame, and digitally generates product placements within the video.

Amazon has been investing in the area too. Their Virtual Product Placement (VPP) platform is currently in its beta phase of development and allows brands to insert their products into a scene – so if there’s an empty bowl on a coffee table, a chocolate bar brand can choose to buy the space and the empty bowl would be filled with their product.

Amazon’s involvement is particularly interesting. They make and deliver their own content on Amazon Prime Video, and if you can replace a product in a bowl, or redecorate a shop-front in the background of a scene, that has massive implications for advertising in movies and streaming shows.

Product placement could become a digital advertising space much like any other. We might start seeing product placements changing from one week to the next and one region to another. The Bud Light truck could feasibly become a Tooheys New truck when the film is shown in our market. I’d imagine the ideal scenario for Amazon is for product placement to become a biddable advertising format, much like Google’s keywords.

And as a digital platform, the space could be fed through a Facebook-esque audience profiler. Amazon already knows your buying behavior after all. As one of the pioneers of ‘you might also like…’ advertising, they could well change a scene’s bookshelf to match your Amazon wishlist.

While the possibilities on the future of product placement for brands are yet to be fully realized, the evidence indicates while it can be effective, subtlety is the key to influence skeptical and cynical audiences.

This piece was originally published by Mumbrella and was written by Lukass Strungs.